Pre-print by Thrul et al.

A re-analysis of Ferguson’s meta-analysis by Thrul et al. makes many of the same mistakes that RH&S did. They dichotomize time again to show that effects after one week are positive and effects less than one week are negative. Aside from the fact that there were errors in the data base, dichotomizing time is virtually never a good modeling approach. The one-week cut-point differed from Haidt, Rausch, and Stein’s cut-point of 2 weeks. In my last post on this debate, I demonstrated how RH&S’s cut-point of 2 weeks is arbitrary and prone to nose mining (if I change the cut-point to greater than two weeks rather than 2 weeks or greater the effect size changes considerably, around a ~50% decrease).

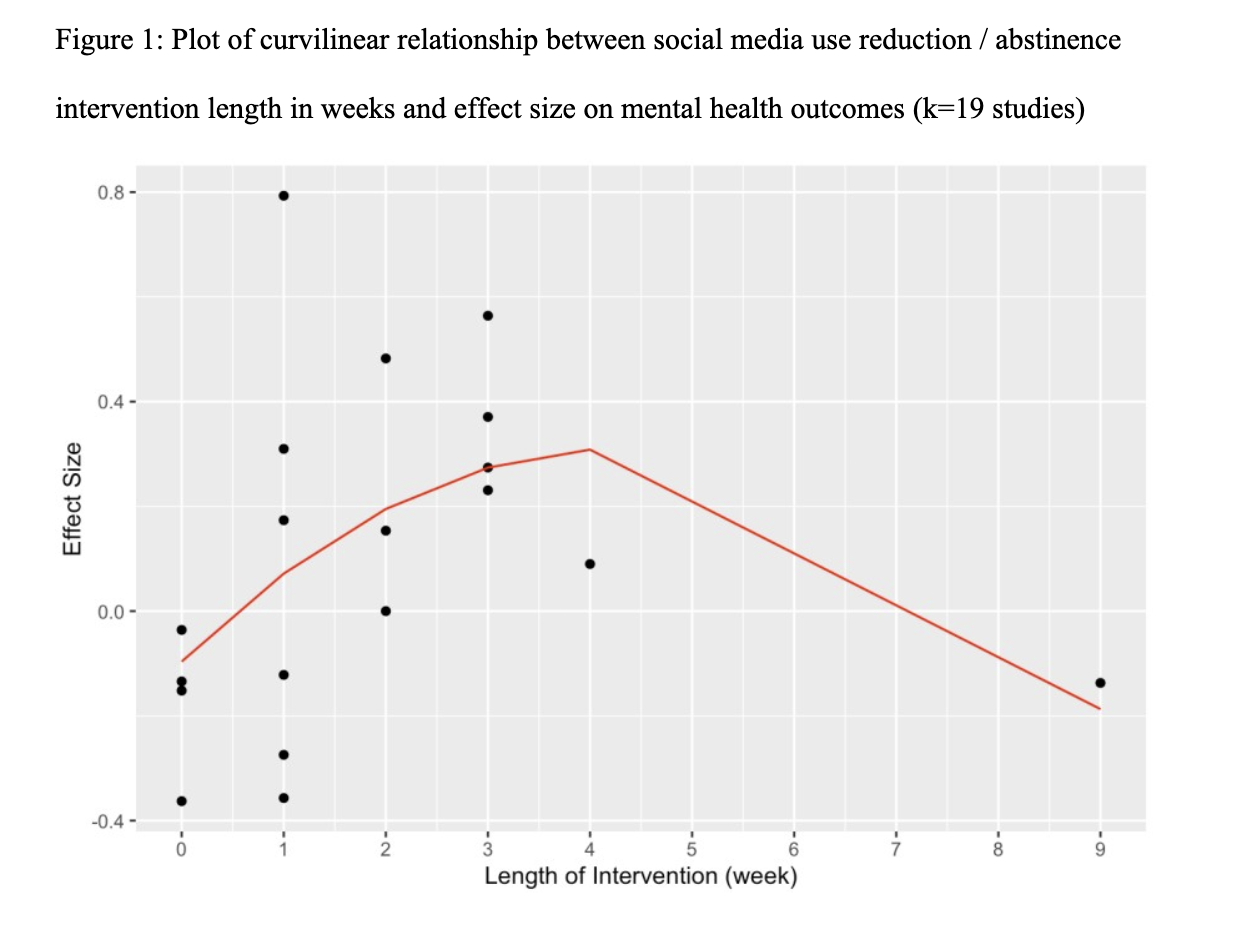

As for their non-linear model (which is almost identical to what I did in my second post almost a month ago), it is unclear what their model is? Also, there are no confidence intervals or prediction intervals and the points being the same size makes it seem like they did not weight it?

This is the entire methods section from Thrul et al.:

We used the information available on the OSF platform related to the original meta-analysis (https://osf.io/jcha2). We then reviewed all included studies (https://osf.io/27dx6). Of the 27 originally included studies, we excluded 7 studies because they were not reduction / abstinence interventions (see online supplement). For example, these studies tested the psychological impact of short sessions of social media use (e.g., active vs. passive use; browsing vs. communicating) (Yuen et al., 2019). We extracted the length of intervention for all studies and categorized them into studies that intervened on social media use for less than 1 week vs. 1 week or longer (see online supplement). Moreover, we also tested intervention length as a continuous variable, using number of weeks as well as number of days as moderator and testing curvilinear relationships by including quadratic terms. All effect sizes were taken from the OSF platform. Random-effects models were estimated using the metafor package in R.

This paper has been accepted at Psychology of Popular Media. This paper contains results based on incorrect data, unclear methods, and artificial dichotomization. I do not think it should be published. I will be writing a more formal response, soon.

Jonathan Haidt then uses this meta-analysis, ignores the curvilinear relationship and then makes a tweet stating:

A new meta-analysis, in press, from @drjthrul et al, using data from the @CJFerguson1111 analysis, finds that “interventions of less than 1 week resulted in significantly worse mental health outcomes (d=-0.168, SE=0.058, p=.004), while interventions of 1 week or longer resulted in significant improvements (d=0.169, SE=0.065, p=.01). Researchers and journalist should stop saying that the evidence is”just correlational.” There is experimental evidence too. We can certainly debate what this all means, but there is a body of experiments that points, pretty consistently, to benefits from reducing social media use, as long as the reduction goes on long enough to get past withdrawal effects.

Of course, this is using, yet again, an arbitrary cut-point to prove the same point and analyzed on a database with incorrect effect sizes. I have modeled it continuously and now with the new living meta, this should be abundantly clear. I followed up to his tweet with the following reply:

;document.getElementById("tweet-50777").innerHTML = tweet["html"];

Anyways, that is it from me. Here is a much nicer note about causality in these RCTs from Stephen J. Wild.

A note on causality in these RCTs (by Stephen J. Wild)

Figuring out the causal effect social media and mental health is difficult. Social media affects mental health through both direct and indirect paths, some of which we can close in reduction or exposure experiments, and some of which we can’t. On top of everything below, we have the usual internal and external validity threats. Among the two biggest issues that likely affect the Ferguson meta-analysis, we cannot agree on the definition of social media or social media use and we do not have a clear and well-measured outcome. Even when we do a well-designed and executed experiment, a number of other challenges threaten our attempts at causal inference.

First we have interference and spillovers, where the causal effect of our exposure affects units other than the unit under study. For social media, it means that social media use doesn’t just affect the person in the study, but also affects their friends and family. Second is effect heterogeneity and the power of our study. We can and should expect social media to affect different groups differently. Yet many of our studies are not powered to detect small effects, let alone small effects in different subgroups. Third is statistical under or over control, where we include the wrong control variables. We include colliders where we shouldn’t, mediators that block the causal path, and fail to include confounders where we should. Fourth includes failure to account for feedback loops, where our exposure (social media) influences our outcome (mental health), which in turn affects our exposure (we have worse mental health so in turn use more social media, and repeat). And a fifth reason involves substitution effects and the proper attribution of causality. When we reduce our social media use, we increase our time spent on other activities. Is the causal effect due to reduced social media use, or an increase in the other activities?

Session Info

R version 4.4.0 (2024-04-24)

Platform: aarch64-apple-darwin20

Running under: macOS Sonoma 14.1

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.4-arm64/Resources/lib/libRblas.0.dylib

LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.4-arm64/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib; LAPACK version 3.12.0

locale:

[1] en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/C/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8

time zone: America/New_York

tzcode source: internal

attached base packages:

[1] stats graphics grDevices datasets utils methods base

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] htmlwidgets_1.6.4 compiler_4.4.0 fastmap_1.2.0 cli_3.6.3

[5] htmltools_0.5.8.1 tools_4.4.0 rstudioapi_0.16.0 yaml_2.3.8

[9] rmarkdown_2.27 knitr_1.47 jsonlite_1.8.8 xfun_0.45

[13] digest_0.6.36 rlang_1.1.4 renv_0.17.3 evaluate_0.24.0

Citing R packages

The following packages were used in this post:

References

Bürkner, Paul-Christian. 2021.

“Bayesian Item Response Modeling in R with brms and Stan.” Journal of Statistical Software 100 (5): 1–54.

https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v100.i05.

Kay, Matthew. 2023.

“Ggdist: Visualizations of Distributions and Uncertainty in the Grammar of Graphics.” https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/2gsz6.

———. 2024.

tidybayes: Tidy Data and Geoms for Bayesian Models.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1308151.

R Core Team. 2024.

R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

https://www.R-project.org/.

Wickham, Hadley. 2023.

Modelr: Modelling Functions That Work with the Pipe.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=modelr.

Wickham, Hadley, Mara Averick, Jennifer Bryan, Winston Chang, Lucy D’Agostino McGowan, Romain François, Garrett Grolemund, et al. 2019.

“Welcome to the tidyverse.” Journal of Open Source Software 4 (43): 1686.

https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686.